Exhibition: Our Georgia, 1987–2007, Part Two

Our Georgia, 1987–2007: Exploring the Georgia Traditional Arts Research Collection

Part 2: Foodways and Material Culture

This exhibition focuses on Georgia’s foodways and material culture, two categories in which traditional artists craft something tangible. “Foodways” refers to what and how people eat. “Material culture” refers to the things people make. The 20 years of foodways and material culture documented by folklorists in the Georgia Traditional Arts Research Collection, available at the Digital Library of Georgia, represent a variety of ethnic and cultural traditions, helping to answer the questions Who are Georgians? and What does it mean to be a Georgian?

Foodways

Everyone must eat, but what we choose to eat is a reflection of identity. While food sustains bodies, foodways―the practices related to selecting, preparing, serving, and eating food―sustain cultural traditions, group identity, and religious beliefs. Foodways differ based on country, region, ethnicity, religion, community, family, and other cultural groupings.

What, when, and how we eat is a way that we share information about who we are. When people leave their home, it is their food traditions that they are most likely to keep with them in their new location. Preparing and enjoying food from home is a way to keep it alive, even when far away. And yet, the history of Georgia’s people and foodways is a complex story of the blending of cultures over hundreds of years based on what food is available and the influence of other communities. These changes to foodways become part of a group’s story.

Foodways and the Environment

Southern food, said to have arisen out of contact between Native Americans, white Europeans, and enslaved Africans in the eighteenth century, is often credited as a starting point to which later immigrants contributed. In fact, the story of Georgia’s foodways begins before European contact with the state’s native bounty: seafood was a plentiful food source, thanks to a coastline that measures roughly 100 miles and comprises saltwater marshes, rivers, streams, swamps, estuaries, and beaches.

Georgia’s Coastal Plain region, which extends from the Atlantic Ocean northward to the Fall Line and west and south to the Alabama and Florida borders respectively, is rich with fossil evidence that suggests the presence of marine life over tens of millions of years. Over time the coastline receded, but when Native Americans arrived in Georgia roughly 12,000 years ago, they were sustained in part by the available bounty.

Piles of shells, mostly from oysters, with bits of plant material and other waste, have been found in various locations along the coast of Georgia. These piles, called shell rings, tell us that oysters were consumed by Native Americans in the area as far back as 4,000 years ago. It is believed that the tradition of roasting oysters over a rock-lined pit dug into the ground originated with Native Americans. The practice of roasting oysters, as well as turning to the water for sustenance, has survived for millennia and continues today. To many coastal communities in Georgia, the cooler months of the year offer an opportunity to engage in the tradition of a community oyster roast (like the long-standing Knights of Columbus event in Brunswick).

How people roast oysters can vary. One way is to dig a large pit (some do this on the beach), line the pit with rocks or cinder blocks, place sheet metal or a grate over the pit, spread oysters in one layer atop the grate, and throw burlap sacks soaked in water over the oysters to allow them to steam. The process for doing an oyster roast typically is based on information that has been handed down among families over generations.

Seafood is Georgia’s native bounty; pork, successfully raised in Georgia for hundreds of years, is the state’s nearly native bounty. Spanish explorers of the land that would become Georgia observed Native Americans using a wooden framework to cook game meat over an open flame. The Spaniards called the wooden apparatus a barbacoa, and thus gave us the word for barbecue. Georgians’ predilection for barbecued pork has been centuries in the making.

Unlike the seafood to be found in Georgia waters, pork was an import, albeit an early one. Originally imported to Florida as early as the mid–sixteenth century by Spanish explorers, hogs had spread to Georgia by the eighteenth century. Though the presence of hogs in Georgia initially posed difficulties (Oglethorpe famously had a number of hogs destroyed after they damaged the fortifications of Fort Frederica), colonists came to rely upon them as a food source and eventually sought greater control of the free-ranging animals. After a period during which farmers supplemented their hogs’ diets, around the mid-nineteenth century they actively sought to improve the quality of their stock through animal husbandry and regular feedings. By this time pork had become a regular, reliable part of Georgians’ diets, positioning barbecue, meat rubbed with various combinations of spices or marinades, to become the staple it is today.

Foodways and Ancestry

Though foodways evolve, they also persist. Over time, an oyster roast became part of the culture of both the Knights of Columbus group and the wider community that looked forward to it each year. Personal relationships, so critical to the transmission of traditional arts, are an important reason why foodways persist. Families are the first groups with whom food is shared, and older family members are reliably the sources from whom recipes and techniques are learned. When families immigrate to the United States, they bring with them, and often maintain, the foodways of their country of origin.

In 1988 folklorist Martha Nelson interviewed Beatriz Patino in the Atlanta home she shared with her husband, Jairo, and their children, Erica, Santiago, Alejandro, and Carolina. Two years previously the family moved from Miami, Florida, where they had lived since arriving from Colombia in 1979. Only Beatriz, Jairo, Erica, and Santiago made that trip; Alejandro and Carolina were both born in the United States. The mother of two natural-born U.S. citizens, Beatriz herself was born and raised in Medellín. She was thirty-three years old at the time the family moved to Miami.

For the Patinos, the decision to leave Colombia was not a decision to abandon their homeland and traditions. These they kept alive by surrounding themselves with such Colombian material culture as the calabazo (a decorated gourd for carrying water), peinilla con vaina (a machete with sheath), and alpargates (shoes worn by peasants), and Beatriz’s traditional cooking. Nearly 2,000 miles and nine years distant from her life in Medellín, Beatriz maintained her connection with Colombia through the familiar compesinos’ (peasant farmers) foodways of Colombia―such as tamales cooked in plantain leaves, fried plantains, fried pork, hominy soup with sugar cane, and meat soup―and ensured her four children would grow up eating those foods just as she and Jairo had.

Foodways and Adaptation

Many immigrants who wish to maintain their native foodways face the issue of availability when they arrive in their new home. Today it’s common to find retailers whose inventory reflects the ingredients of a region or culture; similarly, it’s common to find restaurants serving dishes utilizing those ingredients. During the period the Traditional Arts Research Collection documents, such availability and use of “ethnic” ingredients would have been somewhat less common but not unknown; certainly, from 1987 to 2007 the variety of foodways available in Georgia expanded exponentially with the growth of immigration.

What of immigrant communities without access to familiar ingredients and restaurant meals? A lack of commercial availability needn’t be limiting when individuals have the opportunity to grow their own produce. Seamstress Nang Elliot, born and raised in Thailand, cultivated her own large Thai herb and spice garden at her home in Jesup, Georgia, documented by folklorists.

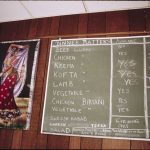

Immigrant foodways become more available as immigrant communities gain financial stability. With economic capital, they are able to open stores and restaurants that make their foodways available to others like themselves and their new community. In the late 1980s, folklorists with the Georgia Folklife Program visited three such establishments. In Decatur, Georgia, JJ’s West Indian Market catered to Caribbean tastes. Tropical Delite Bakery, also in Decatur, specialized in Jamaican foods. In Atlanta’s Midtown neighborhood, Latino’s Café served dishes like empanadas and plantains.

Valuing and maintaining its own foodways doesn’t mean that a community favors them exclusively. When communities meet, people and foodways adapt to new influences. May Moua told folklorist Janice Morrill that her children enjoy such American food as “dessert, fried chicken, hot dogs, hamburgers, cheese, [and] spaghetti,” and she cooked Hmong food only on the weekend. Similarly, in the course of documenting the foodways of employees at Thailand Cleaners, Morrill noted that the daughter of one staff member stated her preference for American food.

Foodways: A Case Study

To answer the questions Who are Georgians? and What does it mean to be a Georgian? in terms of the state’s foodways, consider the case of Risheshwari “Radha” Pandey and her restaurant, Pandey’s, in Albany, Georgia.

Radha Pandey was born in Uttar Pradesh, a north central region of India, in 1941. There, she learned from her mother and grandmother how to cook vegetarian recipes using such ingredients as lentils, beans, cauliflower, and squash. Radha came to the United States for the first time in 1970 with her husband, Vish, but returned to India after he had finished his education. When the Pandeys came back in the 1980s, they settled in Albany and purchased a restaurant with the intention of introducing their community to Indian food―slowly. They called it Pandey’s.

At first, the Pandeys served the same foods the restaurant’s previous owner did: barbecue, fried chicken, fish, hamburgers, and french fries. Soon, customers began asking for the food the Pandeys ate themselves. Proceeding cautiously, Radha adapted a steak sandwich by seasoning it with coriander, cinnamon, cardamom, cloves, ginger, saffron, and turmeric. The sandwich proved popular, and from there, Radha expanded the menu. When folklorist Jan Rosenberg visited Pandey’s two years after it opened, the menu included the same foods the family ate at home. Radha revealed to Rosenberg that her family had recently started eating meat, including hot dogs flavored with Indian spices.

As the Pandeys’ story illustrates, Georgians’ foodways are strongly connected to those of their families and ancestors. They maintain familiar foodways but also adapt to other influences. Over time, Georgians’ tastes evolve, changing the story of the state’s foodways. This is what it means to be Georgian.

Material Culture: Introduction

Material culture, sometimes associated with folk arts and crafts, refers to art objects and the human activities and beliefs connected to them. It includes items large and small in a variety of media, but they can all be touched and seen as opposed to just heard. Items of material culture are influenced by country, region, ethnicity, religion, community, family, and other cultural groupings. A community’s experience may be reflected in its material culture, and the way that material culture evolves may reveal changes in the community.

Today, mass-produced goods are inexpensive and easily accessible, but that wasn’t always the case. Most of the items examined in this digital exhibition evolved from an earlier form of something necessary to daily life that was made by hand. Often, there were no alternatives―or at least no affordable, accessible alternatives―to these handcrafted objects. When the passage of time, including the availability of factory-produced goods, rendered traditional arts like seagrass basketry and utilitarian handmade pottery no longer strictly necessary, traditional artists were faced with a crucible: what role would their creations play in the local community and the wider world?

As factory goods priced traditional artists out of the market as the go-to makers, handmade objects became both rarer and less utilitarian; artistic evolution had always been a matter of course, but as needs changed, makers were able to incorporate more decoration and personal style into their work. Concurrently, the economic and cultural value of the traditional arts changed.

Material Culture and the Environment

Availability matters when it comes to meeting people’s needs, and Georgia’s natural resources have played a role in the development of the state’s material culture. Some traditional arts, like pottery and wood carving, are nearly universal―so long as a community has access to clay and wood. The circumstances within a community that drive the creation of a particular type of pottery or wood carving are unique. In Georgia the abundance or ubiquity of a resource can create circumstances that lead to its adoption as a favored material that is regularly utilized in the production of traditional arts. It can also lead to the recognition of the state or a region within it as a specialist in the production of that traditional art.

Today, nearly two-thirds of Georgia is covered by forest land. This figure has fluctuated over time, both growing and shrinking thanks to the state’s role as a leader in the forest industry. Just as nineteenth-century industrialists recognized the value of the state’s forests, so too did early settlers and traditional artists in every age. Folklorist John Burrison cites woodworking as a traditional art routinely practiced by men in Georgia. Ernie Mills of Perry, Georgia, is one of them.

As a boy, Ernie Mills learned wood carving from his father and grandfather, who first taught him how to whittle, that is, to carve wood into a shape by cutting many small slices from it. Professionally, Ernie worked as an airline flight dispatcher, but continued with wood carving and was able to devote more time to it upon retirement, making it a second career. As a child, his favorite things to carve were animals. As an adult, his love of hunting and of carving led to an interest in crafting duck decoys. Ernie sought out other decoy carvers to learn from, and as he developed his skill, he was able to begin selling them. His talent has been recognized in exhibitions organized by the Atlanta History Center and Smithsonian Institution.

Georgia not only is known for its clay but is the largest producer of this natural resource in the United States. Due to its significant clay sources, Georgia has maintained a substantial pottery tradition for several hundred years. The state’s earliest potters created the storage vessels for food and beverages that Georgia’s farmers needed. Large quantities of stoneware clay, which fires into a sturdy product ideal for the wear and tear of farm life, led to the creation of eight pottery centers that each developed a unique style. Only a few of these family-run pottery businesses continue today.

Meaders Pottery in Cleveland, Georgia, opened in 1892. Generations of family members helped run the shop, including Lanier Meaders. Faithful to the traditional style of the region, Lanier preferred the dark, earthy colors he learned to make when he was young. He became known for his face jugs, which have sold for several thousand dollars, and was recognized with the Governor’s Award for the Arts in Georgia and a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. Members of the Meaders family still make pottery today.

Material Culture and Ancestry

Many Georgians grew up in houses that had handmade quilts on beds and the backs of sofas. To many, quilts are such a regular part of life that they’ve never stopped to consider the history of this beloved traditional art form. While machine-made quilts may be purchased in stores today, for most of history quilts were made by hand. Quilting was born out of the necessity to keep warm. All quilts are made of pieces of fabric stitched together, but the style, colors, type of fabric, and stitching pattern varied depending on the location and financial circumstances of the maker. Quilting styles changed over time, as did the fabrics that were used.

By definition the traditional arts, taught and learned informally, are personal. A quilt is one of the most personal forms of traditional material culture. Quilts are often made by groups of women working together; they are sometimes made from scraps of the quilter’s old clothing; and they are meant to come into close contact with the body. When Hazel Fulton of Cartersville, Georgia, sought a connection with her family, she turned to quilting.

Hazel Fulton was thirteen when her mother, Minnie Flanagan Graves, died. Hazel’s sister, Helen, was just nine at the time, and the girls’ father had abandoned the family eight years earlier. Amid this bleakness, Hazel found comfort in the treasured memory of her mother’s quilting. Minnie had been a field laborer by day, and quilted at night. Hazel held the lamp as her mother worked. Minnie and Hazel never sat next to each other, mother critiquing daughter’s technique as she pieced scraps of fabric together, but the box of fabric scraps left behind by her mother inspired an adult Hazel to teach herself, relying on her memories of her mother’s technique and magazine patterns.

Hazel kept quilting as life took her through many other tragedies: the death of two husbands and two of her three children. At the time she was interviewed by folklorist Maggie Holtzberg in 1995, Hazel estimated she had made sixty full-size quilts and twenty-five to thirty crib-size ones. The oldest quilt in Hazel’s possession was one she made as a wedding present for her sister in 1944. Helen had returned it to her sister in good condition in 1988. In notes she made for the Georgia Traditional Arts Collection, Hazel concluded, “As I enter heaven, may the Lord present me with all the quilts I did not make here on earth.”

Material Culture and Adaptation

The quilts, carvings, and pots a community produces are things people can carry with them if they ever leave their homes to start again. In their new home, those quilts, carvings, and pots are expressions of the community and situation from which they came. What they do with these traditional arts and the skills used to create them when they have arrived in a new home is a story of adaptation.

Helda Morales was one of the many Hispanic immigrants who arrived in Georgia in the 1980s. A resident of Chamblee, Morales worked at La Bodeguita, a Hispanic food market. Outside of work, Morales spent time creating needlework. In addition to knitting, crocheting, and embroidering, Morales created arpilleras, which appear at first glance to be quilt-like murals.

Arpilleras (are-pea-air-uhs, meaning “burlap”) are made of cloth that is hand-stitched to burlap backing in order to create a scene that usually tells a story. Most often the story involves rural people who work the land for their living. Arpilleras originated in South America and have been used by women in Chile to tell the story of oppression and violence under a dictatorship. Many art forms, including traditional arts, are used to express opinions and beliefs. Using arpilleras was a subversive yet safe way for many women to express opposition to violent leadership.

The documentation associated with Morales and her arpilleras doesn’t mention where she learned to make them or why, but the facts it does provide do create a simple yet compelling narrative about the way people and traditional arts adapt. Morales came to Georgia from Colombia, not Chile, but the creation of arpilleras was a meaningful South American tradition she brought with her. The arpillera photographed by folklorist Martha Nelson is a rural scene of a potato harvest that does not appear to have any underlying message of protest.

Material Culture: A Case Study

To answer the questions Who are Georgians? and What does it mean to be a Georgian? as they relate to the state’s material culture, consider the traditional art of sweetgrass basketry.

Today sweetgrass baskets made on Sapelo Island are purchased as art by museums and collectors. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, however, the baskets were agricultural tools produced by enslaved West Africans who brought with them knowledge of coiled-grass basketry. Slaves used the baskets to harvest and store rice; plantation owners used the baskets as a commodity, selling baskets made by their slaves as a form of income. The end of slavery is cited as a moment of the baskets’ evolution: though the baskets still retained their original agricultural purpose as many of the African Americans who made them still worked the land, a conscious decision was made by former slaves to maintain the tradition as a way of retaining a relationship to Africa and their ancestors. Over time, the baskets became popular with tourists and a way to earn an income.

Master basketmaker Yvonne Grovner worked as a schoolbus driver and Department of Natural Resources tour guide. For Grover, the additional income from basketmaking was a benefit (she once sold a basket for $600), but she was also passionate about Sapelo Island and maintaining its culture. Grovner learned her craft from an elderly man named Allen Green. Green had learned it from his grandfather, who was born into slavery. At the time of her interview with folklorist Adrienn Mendonca, Grovner had taught classes and worked with five apprentices since mastering sweetgrass basketry herself. One middle-aged apprentice, Jerome, appreciated the opportunity to learn more about the baskets he’d seen all his life but never knew much about. Grover also planned to share her craft with members of the younger generation, including her daughter Monique and cousin Devion Jackson.

The desire of the African American community and Yvonne Grovner herself to maintain the cultural tradition of sweetgrass basketry speaks to the powerful ancestral connection the traditional art offers those who practice it. While the purposes of the baskets and their makers have evolved, their creation is a poignant way of sustaining a community.

Why Traditional Arts Matter

“The value of the baskets increases with age, and with proper care their lifetime is infinite.”

So reads the brochure Yvonne Grovner created to advertise her classes and sweetgrass baskets. As this digital exhibition has illustrated through examples of gardens, tamales, pots, and quilts, with proper care the lifetime of traditional arts is infinite.

Whether foodways or material culture, the traditional arts remain vital, argue folklorists Annie Archbold and Janice Morrill, because makers and consumers find value in them. “The traditional artifact,” they continue, “emerges from and is clearly linked to a specific community setting, [and] continues to act as a message between members of that community.” Georgia’s foodways and material culture speak to members outside of a particular community, too. The curiosity of the patrons of Pandey’s restaurant and the tourists who purchase Yvonne Grovner’s baskets as quickly as she can make them attest to the benefits to be had when one culture shares its values with another.

From the way Georgians take inspiration from their ancestors to the way they maintain their identity through continuous evolutions, Georgians are people who both crave and create meaning, too.

Sources and Further Reading

Archbold, Annie, and Janice Morrill, eds. Georgia Folklife: A Pictorial Essay. Atlanta: Georgia Folklife Program, 1989.

Burrison, John A. Brothers in Clay: The Story of Georgia Folk Pottery. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2008.

Burrison, John A. From Mud to Jug: The Folk Potters and Pottery of Northeast Georgia. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

Burrison, John A. Roots of a Region: Southern Folk Culture. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007.

Georgia Traditional Arts Research Collection

Vlach, John M. The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990.

Funding provided by Georgia Council for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts