Exhibition: Our Georgia, 1987–2007, Part Three

Our Georgia, 1987–2007: Exploring the Georgia Traditional Arts Research Collection

Part 3: Music and Dance

This exhibition focuses on Georgia’s music and dance, two performance-based categories of traditional arts that sometimes overlap. “Foodways” refers to what and how people eat. “Material culture” refers to the things people make. Documented by folklorists for 20 years and now part of the Georgia Traditional Arts Research Collection, available at the Digital Library of Georgia, the forms of music and dance examined here represent a variety of ethnic and cultural traditions, and help to answer the questions Who are Georgians? and What does it mean to be a Georgian?

Case studies focusing on Sacred Harp singing, guzheng player Angela Jui Chen, banjo player Bob Flesher, the McIntosh County Shouters’ ring shout, and Kuchipudi dancer Sasikala Penumarthi reveal insights similar to those seen in foodways and material culture: traditional music and dance are influenced by the environment in which they develop and the environment of their practitioners; they adapt to new circumstances over time; and they are often practiced as a way to connect with one’s ancestors.

Though they illustrate universal truths about the traditional arts, these case studies also speak to a particular moment in time, the late twentieth century, which was a time of growth for Georgia and a fruitful time for traditional artists: A community of professional folklorists that had established itself in the early 1980s was on hand to document the traditional arts as part of an outreach process.

Sacred Harp Singing: Adaptations and Community

Sacred Harp singing, also known as shape-note singing, is a form of unaccompanied vocal music that originated in Europe more than 200 years ago. In an effort to teach those who did not read music, singing masters adopted the practice of using shapes to denote the tones of a musical scale. Unlike choral or gospel singing, Sacred Harp singing is not dominated by a melody that is supported by a harmony; rather, various parts coexist. According to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, “Gapped scales (having less than the usual seven notes) and unusual harmonies help account for [Sacred Harp singing’s] characteristic sound.”

Though Sacred Harp is practiced elsewhere in the United States, Georgians have a special connection to the tradition. In 1844 B. F. White and E. J. King of Georgia published The Sacred Harp, a popular and widely used shape-note songbook. The original songbook has undergone several revisions, but in the twentieth-first century, it is Georgian Hugh McGraw’s 1991 revision that is most widely used today.

The history of Sacred Harp music bridges the secular and the sacred; the songbook contains many nondenominational hymns whose musical origins lay in drinking and work songs.

At the 1987 Chattahoochee Singing Convention, a long-established annual event that brought singers together for music, food, and fellowship, folklorists spoke to McGraw, winner of a National Heritage Fellowship for his work. He explained why Sacred Harp music and the Sacred Harp community were meaningful: “It means good, clean, wholesome recreation. It means good fellowship. It means a spiritual uplift. It means a dinner on the grounds. It’s just my way of life.”

Guzheng

Thousands of years old, the guzheng, or Chinese zither, is a string instrument that is plucked or strummed. In ancient China, the guzheng accompanied poets at the royal court. Angela Jui Chen of Alpharetta was taught to play the guzheng by a master artist when she was young. Chen’s playing was interrupted by the family’s emigration from Taiwan and the demands of raising two young children. After the death of her son, a music lover, Chen turned to the guzheng as a source of comfort. Playing the guzheng provided her with a connection not only to her son but also to her cultural heritage.

Performances at Chinese cultural events such as dragon boat races and lunar new year celebrations allowed Chen to share the guzheng with people to whom the guzheng may have been familiar. Other performances, such as those she gave at events associated with the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games, allowed her to introduce the guzheng to new audiences, reporting to a folklorist, “The guzheng is being widely accepted and people are quick to ask questions and offer compliments. . . . I am enthusiastic about the reception of the music, the opportunities afforded me to play, and the sense of accomplishment that I now have.”

Banjo

Based on stringed instruments played in Africa, the banjo was developed by enslaved Africans. In the early nineteenth century, white Americans played the banjo in minstrel shows, entertainments involving music and acting in which white performers in blackface portrayed black characters as buffoonish and dim-witted. Minstrel shows were not exclusive to Georgia or the South, though it was a Virginian who developed the banjo as we know it today and began using it in minstrel performances. Offensive minstrel shows became extinct, but the banjo’s popularity and influence grew.

According to banjo historian, maker, and player Bob Flesher, of Peachtree City, “The minstrel playing style is the father of old-time mountain music. The folks in the Southern mountains got their music and clawhammer style from the minstrels during and after the Civil War. Before the war, the banjo did not exist in the mountains. For the most part, only minstrels had banjos.” Like minstrel music, old-time music was not unique to the South. With an upbeat tempo that made it an ideal accompaniment to dancing, old-time music was popular in both urban and rural areas of Georgia.

Flesher, a native Californian who came to Georgia through his job as an Eastern Air Lines pilot, devoted himself to music full-time after retirement. As a young man, Flesher had been told his style of playing most closely resembled old-time music. He discovered minstrel music not through a family legacy like other traditional artists, but through research. Enjoying the new dimension it added to his own musicianship, Flesher began performing in the band Dr. Horsehair’s Old-Time Minstrels, which played authentic music and donned reproduction costumes (though not blackface) for performances. He expressed his commitment to the music in an interview with the Banjo Newsletter, archived as part of the Traditional Arts Collection: “These [songs and techniques] are 140 years old and they’ve just been lost somewhere along the way. If we can recapture them, we can keep this old-time style of playing alive and provide a ‘new’ dimension to [it].”

The Ring Shout

The Geechee people of the Georgia coast are the descendants of people from West and Central Africa who were captured and sold into slavery on coastal plantations. The ring shout is a fusion of their African traditions and exposure to the Christian beliefs of plantation owners, and it may be the oldest surviving African American performance tradition. A blend of music and movement, the ring shout involves a circle of people shuffling counterclockwise, clapping in rhythm, while a “stick-man” beats a stick or broom on the wooden floor for percussion. In a practice known as call and response, one person calls out a line of the song and others respond vocally. The ring shout, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, “affirms oneness with the Spirit and with ancestors as well as community cohesiveness” and stands as a forerunner to spirituals and gospel music.

First documented during the Civil War, the ring shout came to the attention of folklorists working in coastal Georgia during the 1930s. The shout came to public prominence when a performance by the McIntosh County Shouters was recorded in 1983. The Shouters were members of Mt. Calvary Baptist Church in Bolden, located near Eulonia. The families of Mt. Calvary had never stopped performing the shout, which they performed annually in commemoration of “Watch Night,” that is, December 31, 1862, the evening on which African Americans gathered in anticipation of the Emancipation Proclamation, which President Abraham Lincoln signed the next day.

The McIntosh County Shouters have had great success, performing at schools, festivals, and concerts. They received Georgia’s Governor’s Award in the Humanities and a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts.

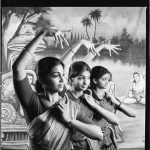

Kuchipudi

Kuchipudi is a 2,000-year-old form of classical dance from India, which conveys stories of Hindu religion and mythology using hand gestures, facial expressions, and footwork. Sasikala Penumarthi, dancer and instructor, joined Atlanta’s growing Hindu community in 1991. Previously, she had studied kuchipudi for six years with renowned teacher Vempati Chinna Satyam in Chennai, India. During this time she gave more than 800 performances, taught workshops, and conducted demonstrations of the art form. In Atlanta, Penumarthi founded the nonprofit Academy of Kuchipudi Dance.

In a 1998 interview with a folklorist, Penumarthi spoke of her hopes for the art form, expressing the importance of maintaining this ancient tradition in the face of a changing India and a growing Indian diaspora. Penumarthi’s student Renuka Raysam valued kuchipudi, she told the folklorist, because of the connection it offered to Indian culture. Student Sudha Natarajam concurred: “You have to keep in touch with your culture. Living in America, you lose a lot.”

Conclusion

In answer to the questions Who are Georgians? and What does it mean to be Georgian?, the ring shout, which commemorates an important date in American history and is performed in schools, provides one powerful suggestion: Georgians are people who value the past but keep their eyes on the future.

Similarly, when banjo player Bob Flesher was asked if he thought the minstrel banjo could make a comeback, he answered in the affirmative, acknowledging the role of the past in shaping the future: “I’m going to continue to promote [minstrel banjos] because minstrel music has such a beautiful sound and is a ‘new’ avenue that clawhammer pickers can use to develop their own style and put renewed life and energy into their playing.”

Anticipating the style’s growth and evolution, Flesher acknowledged an important truth of traditional artistry captured in the intent of the Georgia Traditional Arts Collection itself: the highest form of any traditional art lays not in its past but in its future.

Sources and Further Reading

Archbold, Annie, and Janice Morrill, eds. Georgia Folklife: A Pictorial Essay. Atlanta: Georgia Folklife Program, 1989.

Atlanta Sacred Harp website

Calemine, James. “The McIntosh County Shouters.” The Bitter Southerner (2017).

Cobb, Buell E. The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004.

Georgia Traditional Arts Research Collection

Rosenbaum, Art. Shout Because You’re Free: The African American Ring Shout Tradition in Coastal Georgia. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013.

Funding provided by Georgia Council for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts