Summerville

Summerville, founded in 1838, is the county seat of Chattooga County. Located in northwest Georgia, this town of approximately 4,300 people is home to one of the only functioning train turntables in the country. Folk art enthusiasts travel far and wide to experience “Paradise Garden,” the renowned home and workplace of artist Howard Finster, now a park open to the public.

March 7 – April 18, 2020

Summerville Train Depot

119 E. Washington Street

Summerville, GA 30747

Stories from the Summerville Community

Painter Arthur Ludy Draws Inspiration from Childhood Memories

Arthur Ludy, Summerville

Rural artists often commit community and family history to memory through art. Painter Arthur Ludy, who works in acrylic, draws on his memories growing up in Summerville and puts these scenes of rural life onto canvas.

As a completely self-taught artist, Ludy discovered his love for art at a young age and lists his older sister, alongside artists Renoir and Norman Rockwell, among those who inspired him to become a painter. Now in his sixties, Ludy continues to paint avidly and plans to paint new works inspired by childhood memories of playing outdoor games like marbles and hopscotch.

Some of Ludy’s works are currently at Around Back at Rocky’s Place in Dawsonville.

Howard Finster’s Testament to Southern Storytelling

Howard Finster in Summerville. Image courtesy of the Chattooga County Historical Society.

The Reverend Howard Finster emerged from the rural Appalachian culture of northeast Alabama and northwest Georgia to become one of America’s most important creative personalities in the last quarter of the twentieth century.

Finster was an artist in various visual media as well as a poet and musician whose creative output and cultural influence were enormous. Finster moved to Chattooga County in 1937 with his wife, Pauline, and their first child, where he lived for the rest of his life. Considered one of the most significant and influential artists in Georgia, Finster filled the nearly two-acre plot of his Summerville home with what appeared at first-glance to be junk.

Finster’s proclaimed “Plant Farm Museum” contained plywood and concrete sculptures; walls, buildings, and trellises with “every man-made item”; didactic, humorous, and religious texts and homilies; biblical signs and paintings; canals and ponds; and two towers made of bicycle and lawnmower frames. Finster and the “Plant Farm Museum” received national attention when they were featured in an article discussing self-taught artists in the December 1975 issue of Esquire Magazine—from then on, the “Plant Farm Museum” was renamed “Paradise Garden.”

Gradually his hometown community of Summerville moved from viewing Finster as a local eccentric to counting him as a community asset and instituting a “Howard Finster Day” folk art festival. Finster went on to produce more than 46,000 works before his death in October 2001, and his first nationally-recognized work, now known as “Paradise Garden,” is open to the public and maintained by the Paradise Garden Foundation.

Desegregating Rural Schools

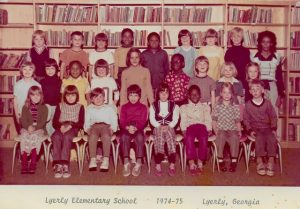

Clemmie Black’s class in 1974 at Lyerly Elementary School. Image courtesy of Clemmie Black.

The United States Supreme Court’s decision in Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, in 1954, ruled school segregation unconstitutional. This ruling may have changed the law on paper, but it was still publicly resisted in some parts of the country. School integration was met with strong opposition throughout the South, including in Georgia.

To avoid integrating schools, Georgia counties built “equalization schools” for African American students, consolidating the smaller black schools. Chattooga County opened Chattooga Training School in 1955, replacing a Rosenwald School which had opened in the Holland community in 1926.

Clemmie Black, now 91 years old, spent her career as a teacher, and she herself experienced the range of educational opportunities available to African Americans in Chattooga County. She graduated from the Holland community’s Rosenwald School in 1946, and went on to attend Fort Valley State College to study education. She began her teaching career at the Rosenwald School from which she graduated, and continued her teaching career at the Chattooga Training School when it opened in 1955.

In 1966, Chattooga County fully integrated its schools, and Black began teaching at Lyerly Elementary School. As a widow with a young son of her own, Clemmie Black was more than a teacher to her students—she was a mother figure. She often used a tin wash pan to provide baths to less-fortunate students, and made sure toiletries, food, and other items were sent home with the students who needed them.

“I continued to work because I felt that I could made a difference,” she asserts, even though she faced objections from fellow teachers, parents, and initially, white students who were uncomfortable with having an African American teacher. Eventually, her expertise in teaching commanded the respect of adults, while her love and attention for each student left a lasting impact on countless lives.

Although she retired in the early 1980s, Clemmie Blacks remains active in her community.

Post Office Paintings

Georgia Countryside (1939), painted by Doris Lee.

Post offices have connected small towns and their residents to the rest of the world long before phones and the Internet. During the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration or WPA formed as part of the New Deal to help job-seekers by providing employment through public-works projects.

Most post office artwork was commissioned through a separate program funded through the Department of the Treasury known as the Section of Painting and Sculpture, later called the Section of Fine Arts. The Section, often confused with the WPA Federal Art Project, was not created to provide economic relief, but instead to create public art to help boost morale in areas hit hard by the Great Depression. It obtained paintings and sculptures through competitions to decorate new federal buildings, primarily post offices and courthouses. The program began in 1934 and operated until 1943, awarding approximately 1,400 contracts for art in federal buildings.

One such contract was awarded to the post office in Summerville. None of the hired artists across the program were local to the areas where the works were commissioned, although many did travel to the communities where their commissioned works would be displayed.

Artist Doris Lee, who painted Georgia Countryside for Summerville’s post office, later said, “I studied the things about Georgia…people from Summerville would come to my studio in New York…they would come and see how it was going and we’d all go out and have lunch.” Doris Lee chose her own subject matter for the mural, and it can still be seen in the Summerville post office today.

Changing Demographics

La Marquensita in Trion, Chattooga County.

Rural communities, particularly in Georgia, have long been a landing place for immigrants who have opened businesses, started local industries, and fashioned new farms. Throughout the last several decades, rural Georgia has seen a growth of Latinx Americans who are helping their small towns survive. In the process, these communities are persisting and bringing new life to their areas.

Chattooga County has welcomed a significant Latinx population, with many of these new residents identifying of Guatemalan and Mexican descent. Many have found success working for the Mt. Vernon Mills in Trion, a major producer in the denim industry. The Latinx population in Chattooga County has furthered shaped the community landscape by opening local grocery stores and restaurants.

To promote cultural understanding and help students adjust to a new community, Chattooga County Schools established a local tradition of celebrating Cinco de Mayo in the schools, including piñatas, food, games, and entertainment.

The “New” Economy of the Rails

Summerville Train Turntable. Image courtesy of the City of Summerville.

Although the number of trains that roar through Georgia’s towns and countryside has declined in the twenty-first century, railroads continue to fuel the economy of rural Georgia through tourism. Railroad depots still dot the old lines, and community members often rally behind preserving these important community landmarks for meeting venues, museums, visitor’s centers, and other purposes. Many communities have revitalized their lines so they might once again benefit the local economy, although now they do so through promoting their tourism industry.

Summerville’s Historic Train Depot and Turntable are a prime example of utilizing the historic railways to new economic benefit. The train depot, constructed around 1917, operated until the mid-1950s. It was purchased by the Chattooga County Historical Society in 1988 and renovated, preserved as a historic site, and is now often used for community events. The train depot is host to Summerville’s Crossroads: Change in Rural America exhibition.

The depot and turntable provide tourism excursions from Chattanooga to Summerville through a partnership with the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum. The 90-ton and 100-foot turntable was transported from Birmingham to Summerville in 1999. It is one of the few surviving turntables still in operation in North America and would have been destroyed if not for the work of community members with the support of the Georgia Department of Transportation and funds from the federal transportation enhancement program.

The turntable now provides visitors with a unique and educational experience while serving the Summerville economy through the expansion of tourism.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Reverend Howard Finster (1915–2001) constructed his first “park,” mainly to fulfill his creative urges and please his family and community. This outdoor museum at his home in Trion featured small replicas of churches and heavenly “mansions.”

Chattooga County is named for the Chattooga River, which flows through the area and is the smaller of two Georgia rivers bearing that name. The larger Chattooga River forms part of the state’s northeast border between Georgia and South Carolina.

Ralph “Country” Brown (1921–1996) grew up in Summerville, and became one of the most popular professional baseball players in Atlanta history. In 1993, Brown was inducted into the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame.

Chattooga County’s largest landowner and major promoter in the nineteenth century, John Fluker Beavers, sold ninety acres for the establishment of the county seat in March 1839. Originally called Selma, the seat was renamed Summerville in 1840 in recognition of its mild climate.